LnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iZGM4NzQ0ZDk2MzZmNjU5YzgwMmI4Y2M3ZDdkNTlmNDAiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfS50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gLnRiLWltYWdlW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaW1hZ2U9ImM1ZDQ3MDcxZTcwN2Q0N2Q4OWJkMmNiNDc2ODU0ZWIxIl0geyBtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDEwMCU7IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA3ODFweCkgeyAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0udGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA1OTlweCkgeyAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0udGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IH0g

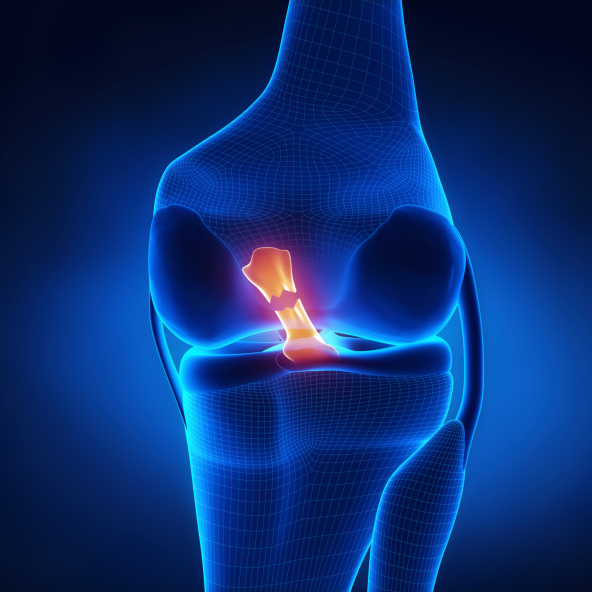

The velocity, power and intensity of women’s sports have considerably amplified over the past decade. Along with the increase in play has also come an increase in injury occurrence. One of the more common injuries is a sprain or rupture of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) of the knee. Female ACL injuries occur six to 10 times more so than males, with many being non-contact injuries (a landing or cutting injury).

There is a great deal of research available on the prevention of ACL injuries, but the way to help eliminate three main problems that can lead to non-contact injuries include ligament dominance, leg dominance and quad dominance.

Ligament dominance

Ligament dominance is when an athlete relies more on their ligaments than their muscles (specifically their hip muscles) to perform athletic tasks such as cutting or landing from a jump. You can see this when an athlete has "Knocked Knees" when they squat or land from a jump, or if they land stiff. This is a very bad situation because it loads up all of the ligaments, especially the ACL.

Leg dominance

Leg dominance is when an athlete relies on one leg more than the other when performing athletic tasks. This can be seen if they lean to one side with a squat or a landing. This is detrimental in that it stresses the leg to the point that an injury can occur.

Quad dominance

Quad dominance is another common injury where an athlete will call on their quadriceps (front of the thigh) muscles before their gluteus maximus (butt/hip) muscles. This is very bad and quite common in females because it increases the shearing force on the ACL and the possibility of an ACL injury.

Other factors that may lead to an ACL injury include:

►Hamstring weakness (very common because the hamstrings protect the ACL), overall ligament instability, Q-angle (shape of the female pelvis), athletic playing style, internal knee anatomy (the size of the notch that the ACL travels through and ACL strength/size) all play a role in potential ACL injuries.

►What can really be improved upon is an athlete’s neuromuscular control. This can be done by training strength, flexibility, balance/proprioception, and simple technique training.

►Jump training and improving an athlete’s ability to land from a jump (landing softer, landing deeper and with the proper contact time—toes before heels and hips before knees) is very important.

►Strength training for the core/hips and hamstrings is very important.

►Emphasizing single leg training with jumps/strengthening to avoid leg dominance.

►Dynamic flexibility prior to training/game and static flexibility post-match/post-game.